3 Days in Jerez

/We didn’t set out to visit Jerez de la Frontera during International Sherry Week. The catalyst was instead a bottle of Lustau Escuadrillo Amontillado—my nightcap this past winter, while my Italian mate, Claudio, stayed true to his Marsala Superiore. Until he tried the Lustau.

The conversion was swift. Two months later, the husband who’d never liked sherry emailed from Italy saying, “Why don’t we take a quick trip to Jerez? There’s a cheap fare from Milan.” $150 on EasyJet for a 2½–hour flight, comparable to New York–Cincinnati. A look at our La Dolce Vita Wine Tours schedule showed we could squeeze in three full days, plus travel.

What can you do in three days in Jerez? I canvassed my wine-industry friends who’d traveled to this corner of southern Spain (thanks May and Lauren and Richard!) and came up with a Top 5 list: Lustau, Gonzales Byass, Bodegas Tradición, and Valdespino in Jerez proper, then Bodegas Hildago/La Gitana in the coastal town of Sanlúcar. Armed with a plan and two partially empty carry-ons, we set off.

Day 1: Valdespino & Bodegas Tradicion

We quickly realized that Jerez has a well-developed tourism industry, and each bodega has a fixed schedule for tours in English, Spanish, and German. Despite the appointments I’d made in advance, we were usually herded into a group tour. So much for my journalist creds.

First up was VALDESPINO. Like many top-tier sherry houses intent on survival, this one is now folded into a larger company, Grupo Estevez, led by Real Tesoro. Here we experienced our first boilerplate bodega tour—educational for sure, but redundant by the second day.

The guide first led us over to a barrique with Plexiglas lid. She pressed a button, and voilá, the barrel was lit from within (a popular trick, we soon learned). Here we could see the white flor, or yeast, growing on the surface of the sherry. (Mysteriously, it develops only in this part of the world—and no one could explain why.)

Flor divides the world of sherry into two. Since anyone can wrap their mind around two parts, this is an easy way to get a handle on sherry and its dizzying array of categories.

The presence or absence of flor results in either biological aging or oxidative aging. Simply put, one group of sherries ages under flor; the other doesn’t. Those that do (fino, manzanilla, amontillado, palo cortado) are protected from oxygen by this Kryptonite yeast barrier, which also chews away at wine’s glycerin, breaking it down and making flor sherry the driest wine in the world.

The other group (oloroso, moscatel, pedro ximénez) demands oxidation, so the flor is immediately killed off by the addition of a higher dose of grape spirits. (For an exhaustive run-down of sherry types and production techniques, see sherry.org.)

Bodega architecture aids these processes. Above-ground cellars promote happy, abundant flor. But to keep temperatures cool during Jerez’s blistering summers, every bodega has a A-frame roof that soars as high as a four-story building. “We call them cathedrals,” said one guide after another. Some have ornate rose windows to press the point. Within such a space, the hot air naturally rises and escapes through rafter-level windows, leaving the air inside a good 20ºF cooler in summer.

Another tour theme was geography: specifically, the two types of soil (albariza and barros and arenas) and the three growing areas (Jerez de la Fontera, Puerto di Santa María, and Sanlúcar de Barrameda). Every bodega also offered an explanation of the solera system (“suelo means soil,” went the refrain), a perpetual blending method with tiered barrel rows that was created in Jerez and later adopted in Marsala.

Exiting Real Tesoro’s aging cellars, our tour continued an unexpected direction. A short walk took us to the stables, home to a dozen sleek black stallions—an extraordinarily beautiful reminder that Andalusia is horse country, too. We stroked the nose of Tio Diego, the sole chestnut, and scooped up four wriggling puppies, still unstable on their feet. Smudged with dirt, we then trudged through a collection of antique horse carriages and Andalusian tackle.

More surprising still was the next stop: an art gallery containing dozens of Picasso prints, mostly from his lusty Minotaur series, plus a few fist-shaking Guernica studies. Though Picasso permanently boycotted Spain after Franco’s rise to power, he’s still a prominent figure here. Bodegas Gonzalez Byass went so far as to ship a barrel to Paris for his signature, and Malaga named its airport after the expat artist.

Everything was turned up a notch at BODEGAS TRADICION—both the sherry aging and the art. They, too, had a gallery, this one filled with museum-worthy canvases by El Greco, Goya, and Velasquez, among others, an astonishing treasure trove for a boutique bodega.

We’d been recommended Bodegas Tradicion because of its unique charter: an exclusive focus on old sherries and brandy. Since its founding in 1998, its owners have sought out 10-year-old casks from other producers, such as F.P. Domecq and the now-defunct Croft, then aged them further, sometimes for decades, producing sherries that might reach an average age of 50. By law, the bodega can’t brag about that on the label. Unlike Portugal, where aged Tawny Ports clearly indicate 10, 20, 30, or 40 Year, sherry has only the VOS and VORS categories, which signify an average of 20 and 30 years respectively. In the case of Bodegas Tradicion’s 50-year-old sherries, you just have to know.

Picks of the day:

Fino Inocente, Valdespino – I’d sampled this single-vineyard Fino at dinner the night before and found it played very well with grilled octopus and roasted vegetables. Tasting it again at the bodega, I was compelled to buy a bottle. (Each purchase was torturously debated, as we’d left room in our luggage for just four bottles.)

Contrabandista Amontillado, Valdespino – On a roll with his new amontillado kick, Claudio dedicated space in his luggage for this winner. It was the prettiest label, to boot.

Moscatel Promesa, Valdespino – Sherry’s 100% muscatels were a complete revelation to us. Made from grapes that had sun-dried for a week, these sweet monovarietal sherries have that same seductive, honeyed, orange-blossom character that runs throughout the Muscat family.

PlTinum Brandy de Jeres, Bodegas Tradicion - A 50-year-old brandy aged in Pedro Ximenez casks, with notes of toasted nut and vanilla, this was smooooth and deep. If I drank brandy, I’d demand this from Santa every year

Day 2: Lustau & Gonzalez Byass

At LUSTAU, we joined yet another group tour, picking up additional details. “You’ll see spider webs in the bodega,” our guide explained, “because spiders eat the insects that eat the wood casks.” We learned that flor subsides in summer and winter, and that each sherry subzone has its own type of flor, which influences flavor. We observed the old railroad tracks that once connected Lustau to the port of Cadiz (much like Haro’s railway lines tied Rioja to the port of Bilbao).

But the most interesting thing at Lustau was its relationship to almancenistas—small, independent bodegas that produce only a few hundred casks. (By comparison, Lustau, a medium-sized firm, ages some 15,000 casks.) Lustau started out in 1896 as one of these almancenistas, selling to the big sherry houses. Today it provides a helping hand to eight of these indie sherry producers by bottling and exporting their unique gems. (Being harder to find in the U.S. than Lustau’s solera reserve line, I bought an Amontillado de Sanlúcar de Barrameda by almacenista Manuel Cuevas Jerada, an amontillado that starts from manzanilla, then is aged in a solera of only 21 butts. A rare treasure indeed.)

GONZALEZ BYASS, in turn, was something we just wanted to experience. To miss it would be like going to Orlando without visiting Disney World. This 42-million-liter firm, which owns 10 percent of the region’s vineyards, makes the world’s most popular sherry, Tio Pepe, which also happens to be Spain’s largest export.

The tour was Disneyfied, but not obnoxiously so. It began with a 15-minute film (narrated by Tio Pepe) that pleasantly encapsulated sherry’s history and the estate’s 19th century beginnings. Next, we boarded a little red choochoo train that carried us from one aging cellar to another. Along the way, we spotted jaunty Tio Pepe logos tucked in the shrubbery and ogled famous signatures on the sherry butts, including Jean Cocteau, Orson Wells, Steven Spielberg, Javier Bardem, and, of course, Pablo Picasso.

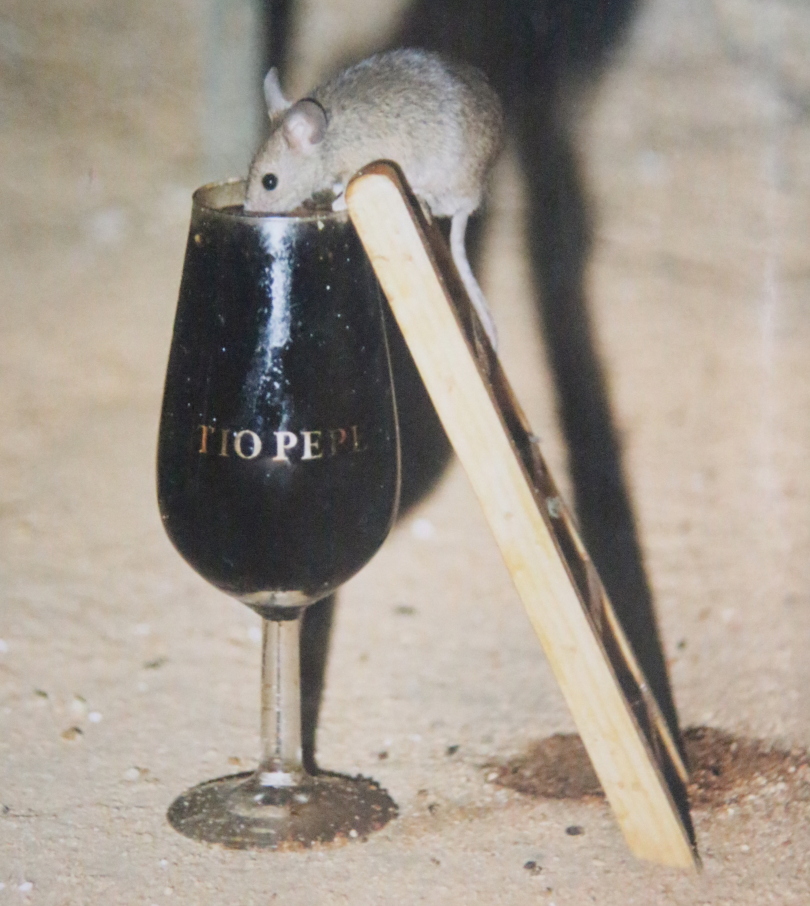

The best part, though, was the mouse ladder. On the floor of one bodega stood a solitary glass filled with sherry. Propped against its rim was a tiny ladder. As the story goes, a caretaker—one José Gálvez—noticed mice eating the crumbs of his meal. He started leaving bigger breadcrumbs, then, thinking any good meal required sherry, dreamed up the mouse ladder. As living proof of its success, several photos showed mice perched atop the ladder, lapping up the sherry. And in the expansive gift shop, kids can ask mommy for a Tio Pepe mouse eraser. Take that, Mickey Mouse!

Picks of the day:

Puerto Fino, Lustau – From the port town of Puerto Santa Maria, this bone-dry fino had appealing petrol notes. Is it the ships?

Very Rare Oloroso Emperatriz Eugenia, Lustau – Dry oloroso was another welcome discovery. This category offers a delicious, oxidized nuttiness that is sometimes even more intense than the amontillados. Named after the wife of Napoleon III, this example was VOS (aged 20 years) and meant to be paired with game or oxtail, a common local dish.

Moscatel Emilín, Lustau – Yet another moscatel that seduced us, from grapes harvested two weeks late.

Day 3: Bodegas Hildago/La Gitana

When BODEGAS HILDAGO moved to its current location in 1850, there was nothing between it and the sea; butts of manzanilla could bath in briny sea breezes for years on end, acquiring that saline kick that manzanilla lovers crave. Gradually the town of Sanlúcar swallowed the bodega whole, so today it sits next to an elongated plaza in the centro that leads to the seaside boardwalk.

“This is not a plastic visit,” Miguel Gutiérrez announces, striding into the shadowy heart of the bodega. We’re thankful to have a private hour after so many groups. Unlike the pretty young things at previous wineries, Gutiérrez is a grey fox who has worked at the bodega for 23 years. Our conversation is unfettered and wanders hither and yon. We hear about Javier Hildago, the charismatic sixth-generation owner, and his days racing horses on the beach in Sanlúcar’s annual Carreras de Caballos. We talk about market trends for sherry, and quiz him about Spain’s perplexing mealtimes. “At 7 o’clock, I’ll have a coffee,” he states. “At 10, I have a breakfast of orange juice, toasted bread, and olive oil. I prepare the body. For me, noon is a good time for amontillado. After, I continue with manzanilla.” We nod, as if this were normal. “The biggest meal of the day is at 4 p.m., then at 10 o’clock I have a light dinner.”

Gutiérrez eventually leads us to a small cask room, where the oldest sherries slumber for up to 45 years. He points towards two rickety rocking chairs. “Relax,” he insists, then grabs a venencia, Jerez’s uniquely shaped wine thief, and plunges it into a cask. “I believe in starting with the oldest wines,” he says, lifting the venencia high above a glass and pouring a perfect stream over a distance of one yard.

This is their Napoleón Amontillado VORS, aged 40-43 years from Manzanilla; it’s the color of burnished gold. “This is very dry, very serious, but very pleasant,” Gutiérrez says, nosing his glass. “Javier’s father would dab some on his handkerchief and say, ‘This is perfume!’” It’s sensational indeed—rich and nutty, with a bone-dry finish (and our fourth acquisition).

More barrel samples follow: Oloroso Faraón VORS, another 40+year treasure, as dry as sherry can be. (“Oloroso should be dry,” Gutiérrez opines. “Some estates leave it a little sweet; I don’t know why. To be sweet, we have cream sherry, with 15% pedro ximenez.”) Then comes a Wellington Palo Cortado VORS (46 years). No spitting is allowed.

In between, Gutiérrez ducks out for a smoke (“For the sherry!” he declares, as if this were a no-brainer). He manages to keep pace with our pours. “I can only imagine how jolly he’ll be at the end of the day, if he keeps this up with other visitors,” Claudio whispers.

And indeed, after an hour, Gutiérrez fetches a group of 12 assorted foreigners. We tag along, going into a larger bodega for barrel samples of their younger wines: a 12-year manzanilla cru called Pastrana, which smacks of the sea and is the loveliest manzanilla we’ve tasted by far. Then there’s the flagship La Gitana Manzanilla, a 5-year version that retains the briny, oxidized flavor of their greater wines. (In the shop, we purchase a half-bottle for a measly 2.50 euros, which we’re drinking tonight with friends in Italy, trying to make converts of them, too.)

Our trip wasn’t all wine. We spent time in Jerez’s spectacular market (“If I lived here, I’d never eat meat again,” said Claudio, lusting after the piles of fresh, glistening fish.) We drove into the mountains outside Jerez, switchbacking through parkland where oaks had been stripped of their bark for cork. We ventured into a maritime park near Sanlúcar, where seabirds flourish and sea salt is made. And every night, we ate very, very well, doubly satisfied that every wine list had a deep by-the-glass sherry selection to play with.

On the plane returning to Milan, Claudio mused, “I can see coming back.” That’s good news. I owe a tip of the hat to Lustau.